Home |

||

|---|---|---|

Before the exhibitions |

Eight Impressionism exhibitions |

After the exhibitions |

|

||

Before the first exhibition

1865 - 1873

The contacts of the painters who are categorised as Impressionists and their circle were diverse. Camille Corot's pupil, Berthe Morisot, joined the circle. However, she found her teacher's style too conventional. Henri Fantin-Latour introduced the painter to Eduard Manet. A close friendship developed. Manet painted Morisot several times, for example in the painting 'Le balcon' (seated in the foreground).

Édouard Manet - Le balcon

1869 - 169 x 125 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

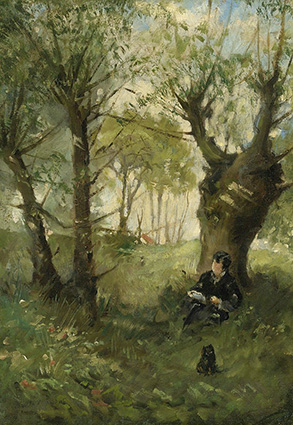

Berthe Morisot - La Lecture.

1869/70 - 101 x 82 cm - Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA >

Some of the painters used the same studio at times or moved to the same place. The exchange was intensive. One meeting place was the Café Guerbois. The café was located near the studios of Édouard Manet and Frédéric Bazille. There was also a shop for artists' supplies opposite. From 1866, fellow painters Henri Fantin-Latour, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Felix Bracquemond, Camille Pissarro and others met at this café alongside Manet and Bazille. Other guests included the sculptor Zacharie Astruc, the photographer Nadar and the writers and art critics Émile Zola, Édmond Duranty and Théodore Duret. Paul Cézanne also made rare appearances at Café Guerbois.

Éduard Manet - Café Guerbois

A Café interior

1869 - 29,5 x 39,5 cm - Black ink on pale brown wove paper, darkened to reddish brown -

Harvard Museum, Cambridge, USA

Henri Fantin-Latour - Un atelier aux Batignolles

1870 - 204 x 273 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

The painter Édouard Manet sits at the easel. Next to Manet is the art critic, painter and sculptor Zacharie Astruc. Behind them, from left to right, are the painters Otto Scholderer and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the art critic and writer Émile Zola, then Edmond Maître, as well as the painters Frédéric Bazille and Claude Monet.

There was much discussion among the artists and even then it was clear that there was no real artistic homogeneity among the group known today as the Impressionists. Their views on painting were too different. If you look at Manet and Degas on the one hand and Monet and Pissarro on the other, for example, this quickly becomes clear. While the latter two were absolutely convinced that one could only really learn to see and paint in nature itself, with its sunlight at different times of day, the former could hardly or not at all be persuaded to leave the studio to paint. What united them was the fight against the established, historically backward-looking pictorial productions of a Cabanel, a Rosa Bonheur and others, who dominated the salons and indulged in the rather superficial view of public taste. This could also be seen in the prices realised for paintings at the time: While perhaps 50 - 100 francs were spent on paintings by Monet or Renoir (some Impressionists occasionally fetched an 'astonishing' 200 francs), most of their paintings were virtually unsaleable, whereas Cabanel and similar 'greats' could easily command 5,000 to 10,000 francs and more.

Édouard Manet - Le petit-déjeuner dans l'atelier

1868 - 118 x 154 cm - Oil on canvas

Neue Pinakothek, München, Germany >

Claude Monet - Femmes au jardin

1866 - 255 x 205 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

Camille Pissarro - Route de Versailles, Louveciennes

1869 - 38 x 46 cm - Oil on canvas

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA >

Berthe Morisot - Le vieux chemin à Auvers

1863 - 45 x 32 cm - Oil on canvas

Private collection

![]()

Here once again, for the sake of differentiation, is the art that was recognised at the time:

Alexandre Cabanel - La mort de Francesca da Rimini et de Paolo Malatesta

1870 - 184 x 255 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

Rosa Bonheur - La foire du cheval

1852/55 - 244 x 506 cm - Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA >

At the Paris Salon of 1874, for example, the following works were exhibited:

Ferdinand Humbert - La Vierge, l'Enfant Jésus et saint Jean-Baptiste

ca. 1874 - 260 x 140 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France >

Jean-Léon Gérôme - L'Eminence Grise

1873 - 69 x 101 cm - Oil on canvas

Museum of Fine Arts Boston, USA >

Henri Gervex - Satyre jouant avec une bacchante

ca. 1874 - 159 x 193 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

Edouard Detaille - Charge du 9e régiment de cuirassiers dans le village de Morsbronn

1874 - 141 x 200 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée Saint-Remi, Reims, France >

![]()

While some of the painters were financially independent, such as Manet, Degas and to some extent Pissarro, others were constantly worried about money. Monet had to flee from his creditors several times during this period. Soon it was no longer a question of financing his painting, but of bare survival. He wrote to Bazille: "Renoir is bringing us bread so that we don't starve." And another time: "We've had no bread, no fire and no light for eight days, it's terrible." As he now also lacked materials, he had to stop his artistic work for a while. Renoir was not much better off; he was in debt to his suppliers.

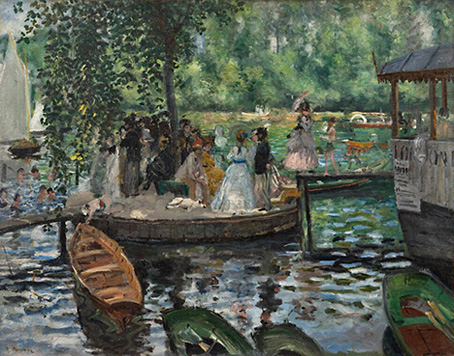

Nevertheless, they did not lose heart. Monet and Renoir often visited 'La Grenouillère', a restaurant and bathing establishment on the Seine. The study of reflections in the water played a major role for both painters. The following two pictures painted on a joint excursion show this.

Claude Monet - La Grenouillère

1869 - 75 x 100 cm - Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA >

(Shown in the second exhibition in 1876 - catalogue no. 164)

Auguste Renoir - La Grenouillère

1869 - 66 x 81 cm - Oil on canvas

Schwedisches Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden >

Frédéric Bazille also devoted himself to painting outdoors. He created the large painting 'The Bathers'. However, a contradiction can be recognised in the treatment of the landscape, which is already worked very freely in lively brushstrokes, and the people, who are painted more or less smoothly.

During this time, Bazille moved to a new studio, where he painted a picture with his fellow painters.

Frédéric Bazille - Les baigneurs

1869 - 160 x 160 cm - Oil on canvas

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, USA >

Frédéric Bazille - Atelier Bazille, Rue de la Condamine

1870 - 98 x 128 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France >

At the time, the artists were generally categorised as belonging to the realism of Courbet and Corot. The term 'Impression' appeared here and there in descriptions, but in 1870 it was not yet directly associated with the group of painters such as Manet, Monet, Renoir or Degas and others.

However, the group's particular style, for example the use of shadows, is very clearly recognisable in these years. The question was often the subject of lively discussions in Café Guerbois. Opinions differed widely, however. Manet said: "... the light appears to him in such a unity that a single tone is enough to represent it and it is better, even if it seems raw, to pass abruptly from light to shadow..." Painters who worked in nature, such as Monet and Pissarro, were opposed to this. In their view, the simple division into illuminated and non-illuminated areas did not exist. For them, shadow areas were not colourless and not simply darker, but rather dark areas with rich hues that appear in complementary colours, especially blue. The pitchy black tones for the shadow areas of the old masters were replaced. Shadows in the snow, for example, are not black, but rather blue, due to the surroundings, the sky.

In 1870, everyone's work became more lively, airy and flooded with light. The depiction of people became more natural...

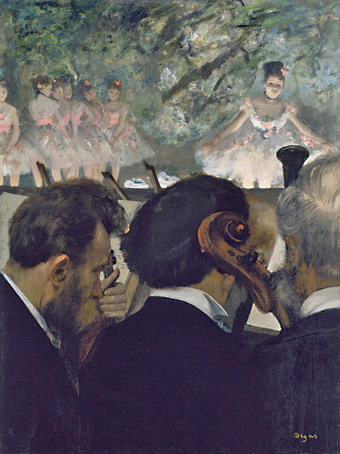

Edgar Degas - Musiciens d'orchestre et ballet

1870 - 69 x 49 cm - Oil on canvas

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany >

Édouard Manet - Dans le jardin

1870 - 44 x 54 cm - Oil on canvas

Shelburne Museum, Vermont, USA

Claude Monet - Sur la plage à Trouville

1870 - 38 x 46 cm - Oil on canvas

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France >

Auguste Renoir - Odalisque

1870 - 69 x 122 cm - Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA >

Berthe Morisott - La robe rose (Albertie-Marguerite Carré)

ca. 1870 - 55 x 67 cm - Oil on canvas

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA >

Auguste Renoir - Promenade

1870 - 81 x 65 cm - Oil on canvas

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA >

The years 1870/1871

The outbreak of hostilities between France and Germany surprised many of the artists in their work and their development towards Impressionism. Bazille joined the army. Renoir was drafted into the cuirassiers and was sent to Bordeaux, where he had to ride horses, although this was new and foreign to him. Degas served in the artillery. Cézanne would also have had to serve in the army, but was ransomed by his father. The military situation in France deteriorated almost daily. The Germans were far superior in terms of numbers and equipment. Pissarro had to leave his accommodation and all his paintings, including those given to him by Monet, had to be left behind. He fled first to Brittany, then to London. As he later learnt, the German military had confiscated his house and the paintings were scattered on the ground in the garden and thus destroyed. After some back and forth, Monet decided to flee to London as well, but left his wife and child behind. Manet had taken his family to the south of France. He also tried to persuade the Morisot family to leave Paris, but they stayed in the city. They experienced the siege of Paris in the winter of 1870/71, which was a time of great hardship for everyone. Food became scarce and expensive, and heating was often unaffordable. Hunger and epidemics were the result.

Bazille fell on 28 November. Monet met Paul Durand-Ruel in London. He was the son of a stationer who also sold painting supplies and ran a small art shop. Durand-Ruel bought several paintings from Monet. Durand-Ruel also bought various paintings from Pissarro in London, but was unable to sell them there.

The Commune was proclaimed in Paris in March 1871. Courbet became a representative of the people. Renoir returned to Paris at this time. Sisley, who was an English citizen, had continued to spend time in France, but the family was ruined by great losses, so that Sisley now had difficulties providing for his family. As far as possible, his fellow painters helped each other out with paints and canvas.

The defeat of the Commune was followed by terrible and very bloody reprisals. Courbet was arrested and sentenced to prison. Manet had returned from the south of France, and Pissarro and Monet also returned from London.

The years that followed would go down in cultural history as the years of the Impressionists. A time in which France was to have the greatest influence on cultural life in Europe, despite its defeat by Germany. But it was many years before the importance of the young painters was recognised in the world, but also in France itself.

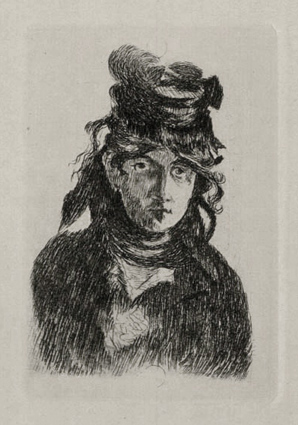

A brief look at the graphic work

before the first Impressionist exhibition

Copperplate engraving, which had dominated art until then, was not suitable for a fast working method due to its difficult and slow processing. Etching was more suitable for the Impressionists. However, printmaking requires a higher degree of imagination and a plan in its execution. For this reason, the attraction of this art form was rather limited for some Impressionists. Claude Monet, for example, was not attracted to it, lacking the spontaneous way of working, while Eduard Manet or Armand Guillaumin devoted themselves to this art of printing. Paul Cézanne rarely utilised the possibilities of etching.

Édouard Manet - Portrait Berthe Morisot

1872 - 12 x 8 cm - Etching

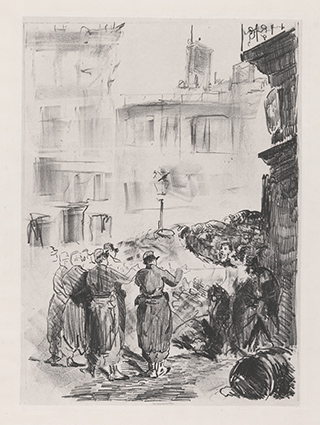

Édouard Manet - Queue in front of the abattoir

1870/71 - 23,8 x 15,9 cm - Etching in brown ink on laid paper

Édouard Manet - Les Courses

1865/72 - 35,8 × 50,9 cm - Lithography

Édouard Manet - La Barricade

1871/73 - 46,7 × 33,2 cm - Lithography

Paul Cézanne - Girl's head

1873 - 31,7 x 22,9 cm - Etching

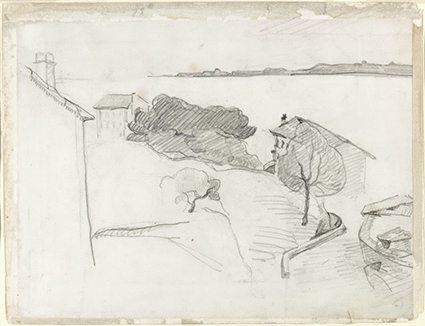

Paul Cézanne - L'Estaque

1870 - 24,3 x 31,6 cm - Graphite on ivory-coloured wove paper

Art Institute of Chicago, USA

Paul Cézanne - Portrait d'un homme barbu

1866 - 23,6 x 17,2 cm - Graphite and black chalk

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Edgar Degas - Ballet dancer in position

ca. 1872/73 - 41 x 27,6 cm - Graphite, chalk on pink wove paper

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, USA

Edgar Degas - Portrait of Julie Burtey

1863/67 - 36,1 × 27,2 cm - Pencil on paper

Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, USA

Edgar Degas - Portrait of the bassist M. Gouffé

1868/69 - 18,8 x 12 cm - Pencil on paper

Private collection

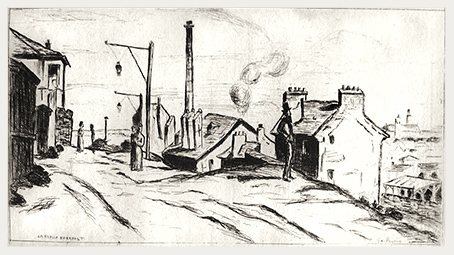

Armand Guillaumin - Rue Barrault

1873 - 9,4 × 17,5 cm - Etching

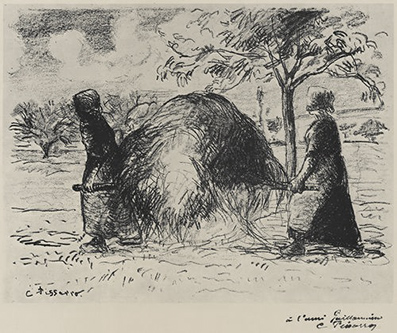

Camille Pissarro - Femmes portant du foin

1874 - 21,5 x 29,2 cm - Lithography

Camille Pissarro - Bosquet d'arbres

1859 - 24 x 31,3 cm - Pencil with brown and graphite on grey paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA